History of the Monastery

Holy King Stefan founded the Dečani Monastery of Christ the Saviour, the most glorious endowment of the rich spiritual and architectural heritage of the Nemanjić dynasty. It was established beside the Bistrica River, beneath the cliffs of the Prokletije Mountains, in a picturesque setting full of forests and flowing waters. An essential part of the Serbian people’s historical memory and spiritual identity lies deeply embedded and forever preserved in its marble walls, magnificent frescoes, and intricate sculptures.

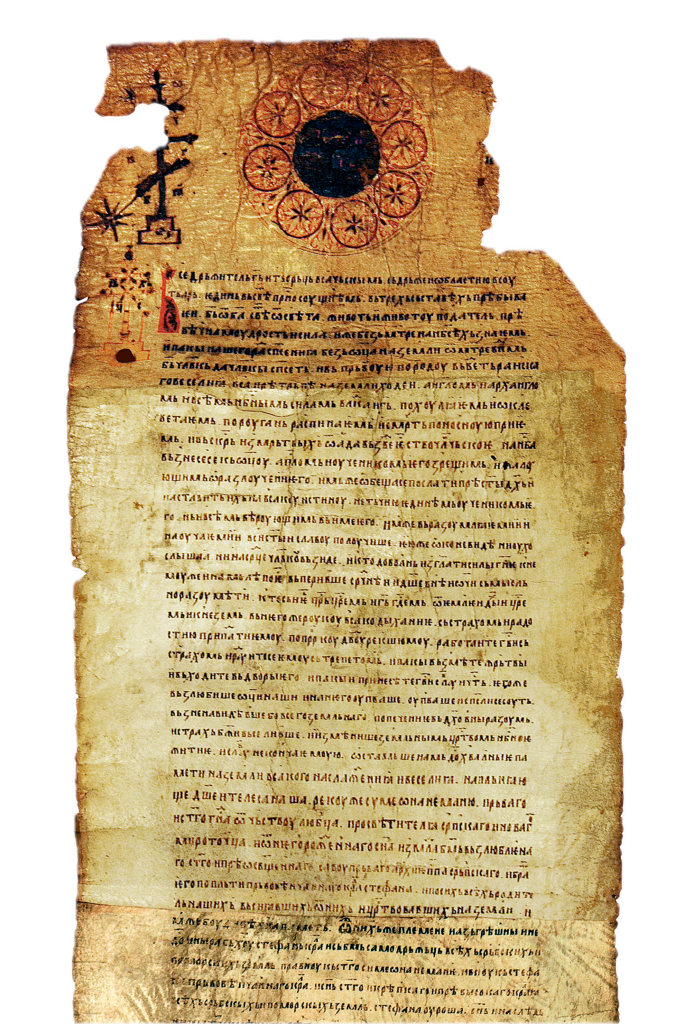

Numerous medieval written records document the life of the Holy King, the Monastery’s estate, and its construction and organisation. Additionally, many documents and records in Serbian, Turkish, and other languages provide insights into the monastery’s later history. These accounts reveal a tumultuous past: the Monastery was almost continuously attacked and looted, then restored and gifted, yet it remained a living witness to the bloody history of the Balkans despite enduring numerous trials.

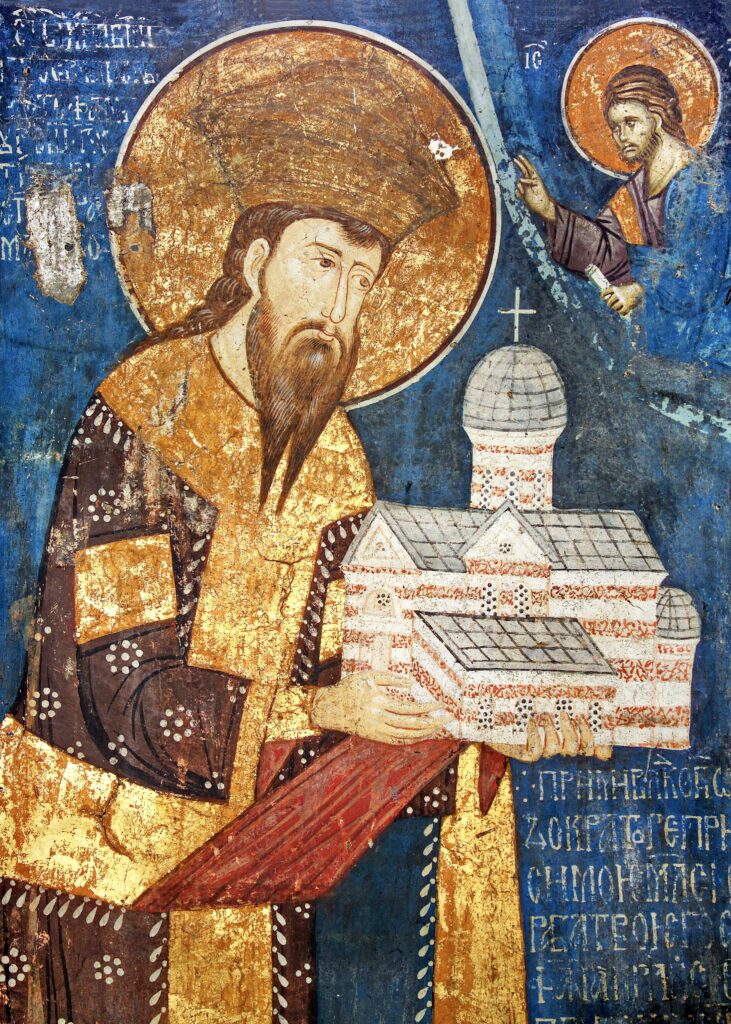

The Monastery’s founder, Saint Stefan Uroš III, known as Stefan Dečanski, who lived between 1285 and 1331, was the son of Holy King Milutin and the father of Emperor Dušan. The Church celebrates him as a great-martyr on November 11/24 (according to the Julian and Gregorian calendars, respectively). At the age of ten, he was given as a hostage to the Tatar Noghay Khan. As a youth, he was falsely accused of attempting to overthrow his father, blinded, and imprisoned in the Monastery of Christ the Pantocrator in Constantinople.

Pious, mild-natured, and compassionate, he won the favour of monks, lords, and Byzantine Emperor Andronicus the Second. Seven years later, following mediation by Serbian and Greek bishops, his father reconciled with him and granted him the rule of the region of Budimlje in today’s Montenegro. In 1321, after the death of King Milutin, Stefan was crowned a king of Serbia in Prizren as Stefan Uroš III. Before his coronation, he removed the bandages from his eyes and revealed his miraculous healing through the intercession of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker. Stefan Uroš III inherited a vast kingdom rich in silver and gold mines, with flourishing agriculture, livestock farming, and commerce. He ruled wisely and piously, loving his people and God.

Holy King Stefan was deeply committed to philanthropic works and the building and decoration of churches in his homeland and beyond–in Jerusalem and the Holy Land, Alexandria, Sinai, Thessaly, Constantinople, and especially on Mount Athos, in today’s Greece, where he generously supported the Monastery of Chilandar. The pinnacle of his endowment efforts was the construction of Dečani Monastery, the largest Serbian medieval monastery.

Gregory Tsamblak described the King’s site selection for the Monastery:

“Whilst visiting many and diverse places in my kingdom, I found a place in the area of Hvosno called Dečani … adorned with every type of tree, for it is a place lush and fertile, and also flat and grassy, and the sweetest waters flow there from every direction; and abundant natural springs surface there, and a crystal-clear river waters it… It is enclosed from the west by the highest of mountains and their steep slopes; hence, the air there is wholesome. A large field adjoins to the east, irrigated by the same river. Such a place is, therefore, good and apt for the construction of a monastery.”

The monastery’s estate was enormous, stretching from the White Drim River in the Prizren Valley in Metohija to Komovi mountains on the present Montenegrin border and from Peć to the Valbona River in Albania. Separate holdings were also in Polimlje, Drenica, near Prizren, and the Bojana River, covering regions in today’s Kosovo, North Albania and western parts of Montenegro.

After choosing the site, Stefan Uroš ordered the area encircled by a rampart fortified with towers adjacent to the monks’ quarters and other monastery buildings. The experienced builder Đorđe and his brothers Dobroslav and Nikola oversaw this work. The master builder, the Franciscan Father Vita, and the stone-cutters from Kotor, on the Montenegrin coast, built the church of the Pantokrator and decorated it with bas-reliefs.

Witnesses to the construction of Dečani Monastery wrote enthusiastically about the craftsmen’s skill in cutting different types of marble and raising the church walls so wondrous and glorious to behold. Father Vita clothed the structure in Western Romanesque-Gothic style. Yet, the interior was entirely adapted to Eastern Orthodox liturgical practices, likely reflecting the influence of Holy Archbishop Daniel II, the King’s chief advisor in this undertaking. The church interior matched its grand external appearance with hewn stone, gold, and precious materials, and it was adorned with liturgical artefacts, gold and silver vessels, vestments, pearls, gemstones, and silk textiles. Stefan Uroš III wrote in his Charter, which has survived to our days:

“I began to build a house of the Lord God – Pantokrator – the All-Maintainer, and upon completing it, I decorated it with every beautiful thing inside and without.”

Unfortunately, the Holy King passed away suddenly and met a martyr’s death before seeing his Monastery completed. In 1331, rebellious nobles, likely with the knowledge of his son Dušan, attacked his summer residence in Nerodimlje in Southern Kosovo. Stefan was imprisoned in the fortress of Zvečan, near today’s Mitrovica, and executed presumably under the orders of Dušan two months later, on November 11/24 according to the modern calendar. His venerable body was transferred to Dečani Monastery and solemnly buried in a prepared tomb. Dušan, as the young King, took responsibility for completing the Monastery and decorating it with frescoes as an act of atonement.

Dušan recorded in his 1343 Charter the miraculous revelation of his father’s holiness. Saint Stefan of Dečani appeared in visions to the church sexton and abbot, instructing them to exhume his remains. The archbishop and Assembly of Bishops prayerfully opened the tomb and found the King’s body intact and fragrant. His holy relics were placed in a reliquary before the iconostasis – the altar screen – and have been a source of miracles ever since, offering healing to those who approach with faith.

THE FIRST ABBOT AND THE EARLY HISTORY OF VISOKI DEČANI MONASTERY

The first abbot of Dečani Monastery, Arsenius, a great ascetic and hermit who lived a life equal to the angels, is mentioned in the Holy King’s Biography. Frescoes depicting his image can still be found in the narthex and altar section of the Monastery church. The image of his successor, Abbot Daniel, is also displayed in the chapel of St. Nicholas within the Monastery. During their time, the Monastery reached the peak of its glory and wealth. Unfortunately, its splendour did not last even an entire century, as it suffered heavily in the aftermath of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 during the wave of advancing Ottoman conquerors.

Princess Milica, who later received monastic tonsure as a nun Eugenia, and her sons, Princes Stefan and Vuk, visited the Monastery and found it deplorable. In her charter, she lamented that “into which the holy founder has invested so much effort . . . has been torched and destroyed by the evil Ishmaelites.” The Lazarević dynasty undertook efforts to restore what had been destroyed, returning the Monastery’s usurped properties and bestowing new gifts. Thanks to them, and later the Brankovich dynasty, Visoki Dečani Monastery continued to be a spiritual and cultural centre of Metohija and home to many educated monks, even during the Ottoman occupation.

OTTOMAN RULE

The Monastery fell under Ottoman rule in 1455 and remained part of the Ottoman Empire until the early twentieth century. Although it lost much of its landholdings, the Monastery retained considerable privileges and gained favour with the Ottoman sultans. According to imperial edicts – firmans – the abbots held the status equal to Ottoman feudal lords and imperial falconers. These titles protected the Monastery under Ottoman law, exempting it from property taxes and granting the abbot the exclusive right to an armed escort during travel. However, local Ottoman feudal lords often ignored these protections, committing acts of violence against the Monastery. The monks of Dečani worked tirelessly to preserve the Monastery and its sacred relics.

Records from old Serbian documents and Ottoman edicts preserved in Istanbul detail the challenges the Monastery’s brotherhood faced. Ottoman sources confirm that violence and property usurpation increased significantly in the latter half of the sixteenth century as the demographics of the villages around the Monastery changed. Serbs who had converted to Islam and immigrants from the Albanian mountains often targeted the Monastery’s lands, showing little regard for its sacred Christian status.

Despite these challenges, restoring the Serb Orthodox Peć Patriarchate in 1557 brought a creative resurgence to the Monastery. Printed liturgical books were acquired, and a large cross and royal doors were made for the iconostasis. The works of Longinus, a Dečani monk renowned for his icon painting and ecclesiastical poetry, also emerged during this period.

TIMES OF WAR AND REBELLION

The Austrian Army’s wars against the Ottomans, coupled with periodic rebellions in the Balkans, often led to harsh Ottoman reprisals against the Serbian population. These included the great migrations of Serbs from Kosovo and Metohija to northern regions across the Sava and Danube Rivers, with the largest migrations occurring in 1690 and 1739. Visoki Dečani was not spared from these turbulent events, suffering episodes of looting, arson, and the torture and murder of its monks.

Despite these hardships, the Holy King Stefan’s cult survived, even among some non-Orthodox Albanians. Written records attest to miracles attributed to St. Stefan, including aiding the destitute, protecting the Monastery, and punishing aggressors.

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AND GROWING CHALLENGES

The nineteenth century brought unrest and wars to the Balkans, intensifying the Monastery’s struggles. The local Ottoman administration’s repressive measures against Christians were acutely felt at Dečani Monastery, too. Metropolitan Zacharias was imprisoned, and several Dečani monks were killed in 1821. By the mid-nineteenth century, violence had become unbearable. The Dečani brotherhood wrote letters pleading with Serbian princes and Russian emperors for protection from Albanian attacks and Roman Catholic Austrian agents who sought to proselytize and offered sponsorship in exchange for union with the Roman Catholic Church.

The Serbo-Turkish Wars (1876–1878) and the founding of the Albanian League in Prizren (1878) brought new turmoil, including pogroms that decimated the Serbian population in surrounding villages. The international rivalry between Austro-Hungary and the Russian Empire over influence in Old Serbian and Macedonian Ottoman domains further complicated the position of the Serbian population. Even distinguished abbots and archimandrites like Seraphim Ristić, Sava of Dečani, and Raphael Matinac struggled to alleviate the Monastery’s challenges.

The Commemoration Book of Dečani Monastery contains entries documenting the era’s violence perpetrated by local Albanian clans. Despite this, some Albanian Muslim families protected the monastery and opposed the aggressors.

Freedom finally came to Visoki Dečani during the Balkan Wars in 1912. The Montenegrin Army, led by General Janko Vukotić, defeated Ottoman ethnic Albanian forces and solemnly entered the Monastery on November 20, 1912, venerating the holy relics of Saint Stefan of Dečani.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR AND BEYOND

During the First World War, following the defeat of the Serbian and Montenegrin armies in the autumn of 1915 and their withdrawal through Albania, Dečani Monastery was occupied by the Bulgarian Army. Bulgarian soldiers took away to Bulgaria some of the Monastery’s precious artefacts and even attempted to take away the holy relics of Saint Stefan to Bulgaria. Written accounts describe how the wagon carrying the King’s relics could not move beyond Dečani’s property and had to be returned. Austrian forces replaced the Bulgarians and imprisoned Russian monks who had arrived from Mount Athos, Greece and resided in Dečani for several years. During the remaining First World War years, the Monastery was converted into a military warehouse.

Freedom was restored to Dečani on October 12, 1918, by Serbian military leader Kosta Pećanac and his volunteer guard. Upon assuming administration, the new abbot, Archimandrite Leontije Ninković, described the Monastery’s condition:

“Dečani Monastery residential quarters were desolate in every sense. The cells were looted and stripped to the bare walls and roof; the floors were full of holes; the doors were in disrepair; the windows were broken; the gardens were fenceless; the fruit trees were damaged…”

The abbot began repairs, recovered some Monastery holdings through legal action, and secured the sponsorship of King Aleksandar Karadjordjević of Yugoslavia, who visited Dečani in 1924 with Queen Maria. Comprehensive restoration efforts were carried out during the decade preceding the Second World War, aided by scholars such as Lazar Mirković, Đurđe Bošković, and Vladimir Petković, who researched and documented the Monastery’s history.

The German Army entered Dečani during the Second World War on Easter, April 20, 1941. Soon after, Italian Carabinieri replaced them and guarded the Monastery against attacks by Albanian fascist collaborationists throughout the war. After the war, the atheist Communist government of Yugoslavia confiscated approximately 800 hectares of fertile land and forests from the Monastery. Nevertheless, church life persisted due to the tireless efforts of abbots Archimandrite Makarije Popović and his successor, Archimandrite Justin Tasić. With the support of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments in Belgrade, significant work was done to conserve and restore the Monastery’s priceless antiquities.

During the Kosovo war in 1999, Dečani Monastery led by Abbots Teodosije and Sava continued to oppose ethnic violence and provided shelter to refugees of all ethnic backgrounds: Albanians, Serbs, and Roma. The Monastery has remained guarded by the NATO-led international peacekeeping forces KFOR since 1999 due to four armed attacks by local extremists and the unstable situation. Nevertheless, the Monastery remains a destination for many visitors and people of goodwill regardless of origin and religion. It was built as a house of God and peace and remains faithful to this testimony as wished by its founder, Saint King Stefan of Dečani.